Manuel Eisner is a Professor of Comparative and Developmental Criminology and Deputy Director of the University of Cambridge Institute of Criminology. He studied the history of crime from the thirteenth century until the end of the twentieth. This is a very short summary about his extraordinary work, which is published by the Department of Sociology at the University of Calgary.

Historical Trends between 1300 and 2000

The sudden decline in homicide [1630 to 1800) did not correlate with improved economic circumstances, stronger courts, or better policing.

Declines in homicide rates primarily resulted from some degree of pacification of encounters in public space, a reluctance to engage in physical confrontation over conflicts, and the waning of honour as a cultural code regulating everyday behaviour.

[A] large number of recent survey studies find that violence is correlated with low autonomy, unstable self-esteem, a high dependence on recognition by others, and limited competence in coping with conflict.

Historical Trends between 1300 and 2000

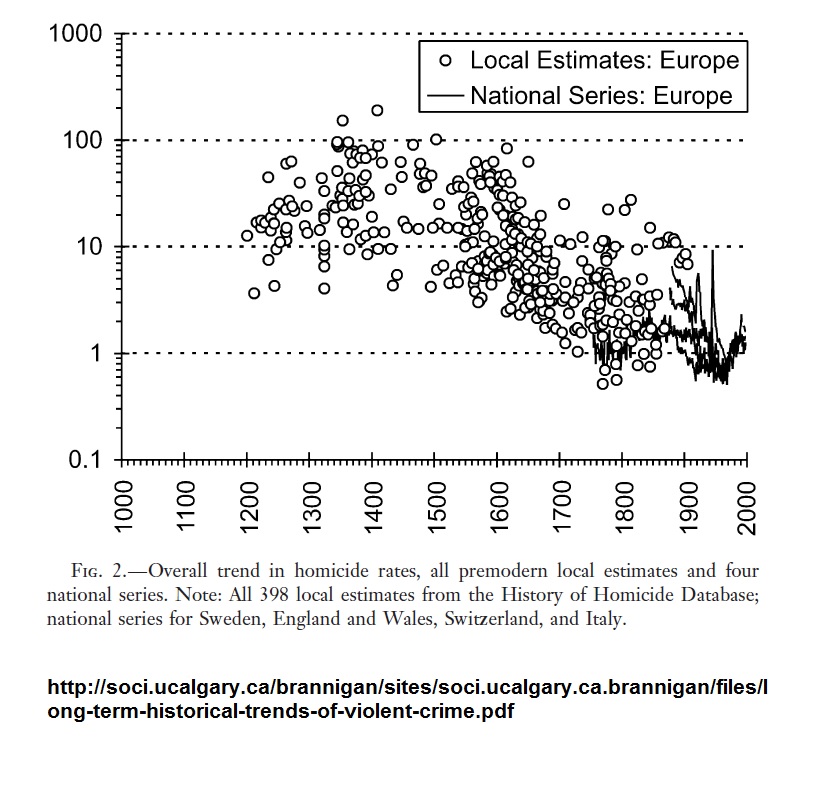

The data suggest a dramatic drop in the fifteenth century and in the twentieth century. The first drop may reflect missing or different sources. For the second drop medical technology have had a major impact. Deaths which occur within the first two hours after the injury may not be cured by modern medical treatment. But most of the deaths occurring after twenty-four hours can now be prevented.

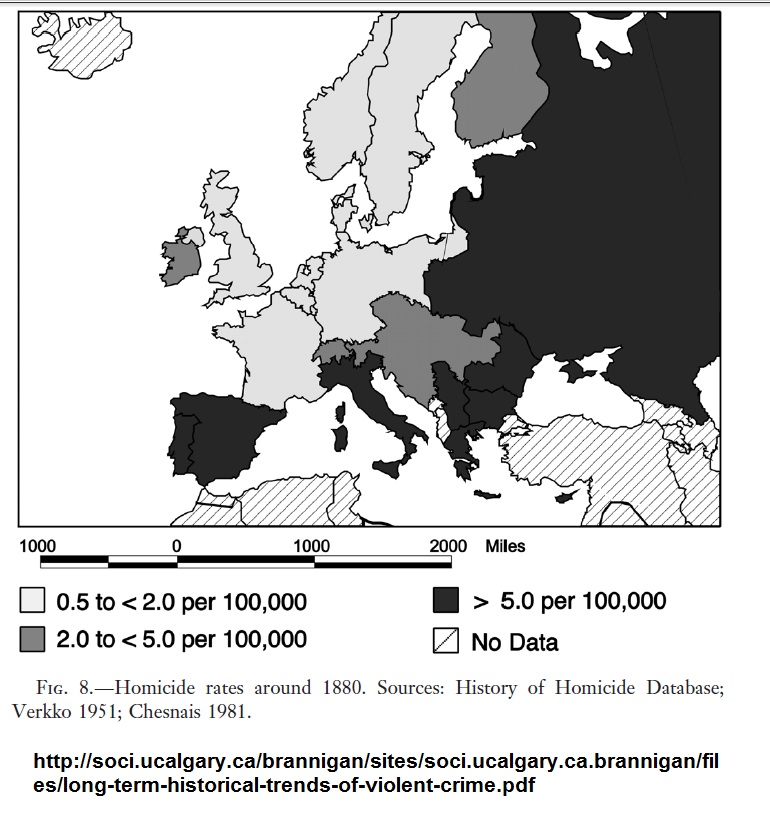

The European countries developed differently In the nineteenth century: The highly industrialized countries of northern Europe, including Germany and France, had low homicide rates and were surrounded by a ring of high-homicide countries: Portugal, Spain, Italy, Greece, Finland and all eastern European countries.

Conclusiones

- There have been only little change in the sex and age structure of serious violent offenders.

- Serious interpersonal criminal violence has declined considerably (1500-1950)

- This drop differed in time and pace, in some areas early and constantly (England, the Netherlands) – in others later and dramatically (Italy).

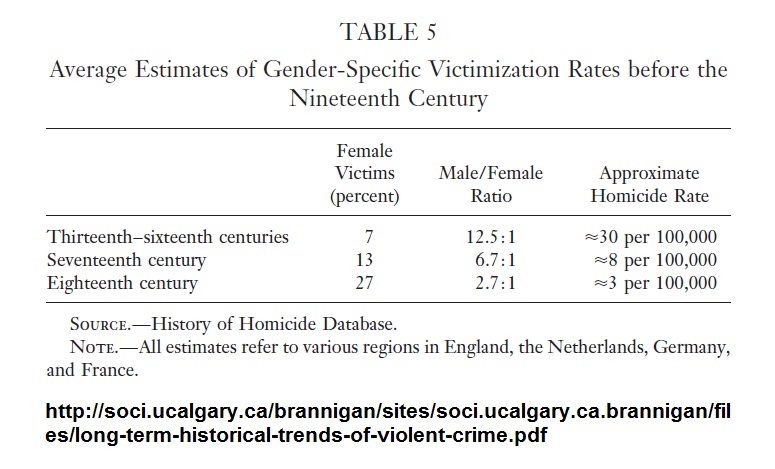

- The drop regularly appears to coincide with a decline in the proportion of male-to-male killings and to be inversely related to a (relative) increase in family homicides.

The Past 120 Years: 1880 – 2000

|

|

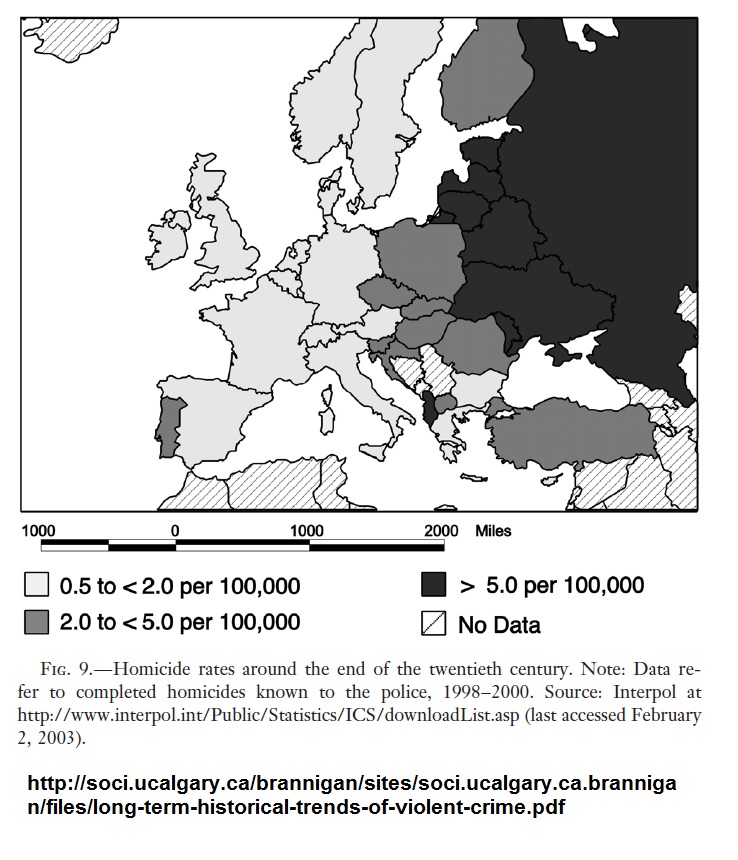

During the past 120 years the southern European countries developed the same low homicide rates as the northern ones. Only the levels in eastern Europe remained high.

Even within the countries of the ninetieth-century regional differences appear to be similar. The homicide rates in Italy were higher in the rural south than in the industrialized north. Same with the South and North of France and different regions in Germany, Poland and Switzerland.

Homicide was low in the centres of modernization characterized by high urbanization, industrialization, literacy, and education. Elevated levels of violence, in turn, were found throughout the peripheral areas with high birth rates, high illiteracy rates, and a predominantly rural population. (page 106)

Between 1880s and 1950s lethal violence fell at least 50 percent in northern European countries and even more in the southern countries.

Between 1950s and 1990s homicide rates increased in most of Europe, also the levels of assault and robbery got an upsurge. He found a similar pattern in uprising between 1790s and 1840s and Roth (2001) researched the sharp increase between 1580s and 1610s.

Long-Term Details

Offenders

Over 800 years the proportion of women committing violent crime (homicide, assault, robbery) was hardly ever above 15 percent and typically ranged between 5 and 12 percent. The same appears with the age of the offenders. Over several centuries the sex differences and age differences of the offenders have remained more or less constant.

Female Victims

During 800 years the average proportions of female victims increased from 7 percent (1300-1700) percent to 27 percent (1800) in modern times. But in modern countries with higher homicide rates (Finland, Serbia, Bulgaria, Italy, and Chile) female victims have the same rate as in the Middle Ages. When lethal violence decline female homicide victims increase. Those suggest that the drop in male-to-male violent encounters have a high impact on lower homicide rates.

Personal Relationship between Offender and Victim

Family homicides was uncommon throughout the Middle Ages (less than 10 percent). During the development to lower overall homicide rates, the share of family killings increased continuously up to 50%. The decline of private revenge (vendetta) is also linked to the overall drop in homicide rates.

Declines in homicide rates primarily resulted from some degree of pacification of encounters in public space, a reluctance to engage in physical confrontation over conflicts, and the waning of honour as a cultural code regulating everyday behaviour.

Reasons

A. The Theory of the Civilizing Process

The rise of monarchic absolutism monopolized violence by central authorities. The nobility (elites) stopped their violent behaviour and increased their affect-control (Elias). Increasing commercialized exchanges of goods needed liberty and trust instead of war with neighbours (Adam Smith.) The court record suggests that more people talked out their differences instead of settling it out with knives, fists and pistols (Beattie).

[M]ost historians of crime would probably agree that the long-term trajectory in homicide rates is an indicator of a wider dynamic that encompasses some sort of pacification of interaction in public space.

B. Social Control

During the Middle Ages homicide was perceived as a result of passion or occurred in defence of honour. Between the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries in continental Europe changed this opion. Now homicide was seen as a crime.

C. Limitations of the ‘‘State Control’’ Model

Muchembled points out that the decline of homicide rates in early modern Europe does not appear to correspond with the rise of the absolutist state. Low Countries show that homicide rates declined in polities where centralized power structures never emerged. No historian believes that the “garrotte among sixteenth- and seventeenth-century European rulers decisively reduced crime”. In the past and in modern times intensified policing and harsh regime of public corporal punishment never lead to lower levels of homicide rates.

‘‘The sudden decline in homicide [1630 to 1800) did not correlate with improved economic circumstances, stronger courts, or better policing. It did, however, correlate with the rise of intense feelings of Protestant and racial solidarity among the colonists, as two wars and a revolution united the formerly divided colonists against New England’s native in habitants, against the French, and against their own Catholic Monarch, James II’’ (Roth)

Honour seems to have a major impact on homicide. In a high-violence society insults lead to personally reaction instead of bringing them to court. Starting in the middle of the seventeenth century verbal violence lost its significance to be defended with every means.

D. Culture

At least two broad cultural streams in Western society may have been associated with the decline in interpersonal violence, namely, Protestantism and modern individualism.

The Protestant ethic’s most important commands were discipline, shame and guilt, as well as human dignity and empathy for the weak.

Furthermore, both Reformation and Counter Reformation brought about an encompassing wave of church religiosity, legitimating the intrusion of clerics into the private sphere but also serving as a backbone of increasing literacy and education.

At the same time (from the sixteenth century onward) started the rise of modern individualism. The individual became freed from its obligation of the group, e.g. vendetta.

To criminologists, the rise of moral individualism should not be an implausible candidate for explaining the fall in criminal violence. Rather, a large number of recent survey studies find that violence is correlated with low autonomy, unstable self-esteem, a high dependence on recognition by others, and limited competence in coping with conflict, which together may well be interpreted as sub dimensions of low moral individualism (Agnew 1994; Baron and Richardson 1994; Heitmeyer 1995). To this we might add the hypothesis that the secular decline of lethal violence occurred when institutional structures and educational practices supported the stabilization of that type of individualized identity that is shaped to meet the challenges of modern life.

Conclusions

Considering the vast field—temporally, geographically, and theoretically— covered in this essay, it may be wise not to attempt an even more condensing conclusion.

About the author

Manuel Eisner conducted an inventive study on levels of homicide throughout Europe over a period of 800 years. He found out that violence and homicide are declining in Europe. His research has highlighted the ways in which cultural models of conduct of life, embedded in social institutions, have shaped patterns of daily behaviour which in turn influenced the likelihood of frictions leading to aggressive behaviour. (Wikipedia)

English

English Deutsch

Deutsch Italiano

Italiano Français

Français Español

Español suomi

suomi Polski

Polski Português

Português Svenska

Svenska český

český Română

Română

One Comment on “Long-Term Historical Trends in Violent Crime”

A worldwide view on violence you can get here:

http://bigthink.com/videos/steven-pinker-on-data-and-the-history-of-violence?